As a medical student without an MD and prescription pad, it can be easy to feel powerless. Asked if it felt like one were making a significant difference in the lives of patients on a day-to-day basis, the answer of almost any medical student would likely be “eh, sometimes.”

We study biochemistry and physiology, memorize treatment regimens for asthma and hypertension, and hold retractors in the operating room, amassing a fund of knowledge that will hopefully– maybe someday– help us care for our patients. We listen to stories, provide emotional support, and occasionally glean information that in some small way improves a patient’s physical condition. And though we learn from and are grateful for the small contributions we are able make on a day-to-day basis, we easily lose perspective at the bottom of the medical education totem pole, forgetting the power we possess when we use our voices collectively. In those moments when we feel we have so little to contribute to patient care, we can look to previous generations of students and trainees for strength and inspiration to affect significant change.

In the 1950s and 60s, for example, students and residents played a critical role in hospital desegregation. While Brown vs. Board of Education made segregation illegal in public schools in 1954, it remained legal to provide or deny healthcare on the basis of race for another decade. The effects of “separate but equal” healthcare were particularly evident in Chicago, where, regardless of the proximity of the nearest hospital or the urgency of a patient’s condition, black patients were taken almost exclusively to Cook County or Provident Hospital. The results of unnecessary transit and delays in care were often catastrophic. Witnessing this injustice, in 1951 a group of residents and students at Cook County Hospital formed the Committee to End Discrimination in Chicago’s Medical Institutions (CEDCMI). Over several years, its members exposed hospitals with discriminatory treatment practices and lobbied medical schools to admit more underrepresented minority students. By revealing data demonstrating the severity of systematic discrimination in Chicago’s hospitals, the CEDCMI successfully convinced the Chicago City Council to enact some of the first legislation to end racist policies in healthcare. This was a crucial moment in shaping a newly emerging, nation-wide movement to desegregate medical practice, ultimately culminating in the inclusion of equal rights to healthcare in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Just as they helped shape and propel the movement for hospital integration, student voices were formative in the effort to end unjust pharmaceutical distribution practices during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. By the late 1980s, HIV/AIDS had become rampant throughout the United States and abroad. For years, the virus was allowed to spread without a known cure, until American drug companies developed effective treatments in the mid 1990s. Despite the discovery of effective medicine, patent laws and profit seeking kept drug prices so high that those in the greatest need of the new therapy had no hope of receiving it, especially in nations like South Africa, where strong political and social forces exerted themselves against fair provision of HIV/AIDS drugs. This fact was not lost on student activists in the United States, who in 1999 joined members of the influential AIDS advocacy organization ACT UP in following Vice President Al Gore across the nation during his campaign for presidency, demanding change in policies that prioritized profits of American pharmaceutical companies over the lives of South Africans suffering from HIV/AIDS. With a great deal of persistence and the disruption of countless campaign events, these students and activists were able to make fair distribution of HIV/AIDS drugs in Africa an important focus of political debate. In the year 2000, their efforts were rewarded by an Executive Order from President Clinton agreeing to hold sub-Saharan nations to less stringent patent law standards, effectively permitting more affordable manufacturing of HIV/AIDS drugs in African nations that needed them most, once again demonstrating the power of the student voice.

While we have come a long way from the segregated hospitals that survived beyond the 1950s and the denial of HIV/AIDS drugs to much of a continent beyond the 1990s, the issue we face now is that of creating a just and equitable healthcare system for all Americans. Though some have benefitted in the recent past from health insurance subsidies, Medicaid expansion, and other provisions of the Affordable Care Act, the provision and receipt of medically necessary care are often still substantially impeded by a patient’s ability to pay.

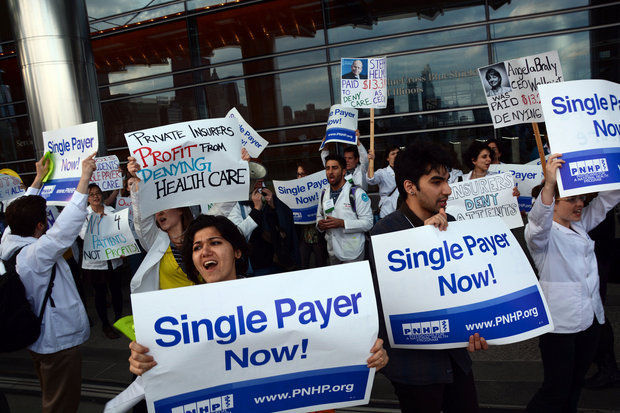

As students, with an abundance of time for patients we are unlikely to see after graduation, we come face to face every day with the fact that it is past time for our country to do away with its costly, confusing, and inefficient employer-sponsored insurance system.. We understand that the best way to increase access, improve quality, and reduce the cost of healthcare is to expand Medicare to all Americans. What we have yet to do is sufficiently educate our communities and legislators in order to convince them of this fact. We, as students, must see this as an opportunity to learn from and join those who came before us in the fight for just and equitable health care for all.

On October 1, 2015, SNaHP chapters across the country will be participating in #TenOne, our Medicare-for-All National Student Day of Action. Each chapter will host its own events to provide education, support legislation, and build the movement for Medicare-for-All. At the end of the day, we will stand in solidarity throughout the nation with candlelight vigils in memory of all those who have lost their lives to un- and under-insurance.

We may not have prescription pads, but history has shown us that students have a voice. Use yours on #TenOne to support #Medicare4All and shape our movement for the future. It’s our turn now.

Janine Petito is a medical student at Boston University School of Medicine.